THE DARK TUNNEL

Part Two

Let’s Talk About the Opening

“Grab with the first line, or at least with the first paragraph.”

Anyone who completed a course in creative writing has heard a variation of this precept. It was true when the first caveman cleared his throat around the fire after the hunt, and in an era of digitally-induced short attention spans, even more so. No matter what your media, if you cannot interest your audience, your story is over before it begins.

If you are not a writer, you may not have noticed this. Browse the shelves of fiction (or good nonfiction, for that matter) in your local bookstore or library, pick some books at random and read the opening paragraph. Whether it’s executed well or badly, you should see at least a conscious attempt to make you want to keep reading.

With this standard in mind, let’s look at how Macdonald opens his very first book:

“Detroit is usually hot and sticky in the summer, and in the winter the snow in the streets is like a dirty, worn-out blanket. Like most other big cities it is best in the fall, where there is still some summer mellowness in the air and the bleak winds have not yet started blowing down the long, wide streets. The heart of the city was clean and sunlit on the September afternoon that Alex Judd and I drove over from Arbana . . .”

Macdonald introduces a story of murder and espionage by talking about the weather. It’s not terrible but it’s a wasted opportunity. And the content is not especially relevant. The book takes place during a few days in September; neither the summer nor the winter have anything to do with the action. Detroit is simply one of many settings, and not the most important one. The geographic center of the story is Arbana, where the campus of Midwestern University is located.

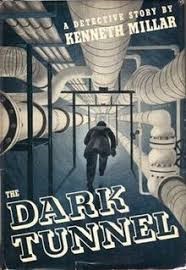

Not only less lurid than the first cover but also more accurate

Who’s on First?

Macdonald recovers nicely from that initial stumble. He understands that he is writing plot-driven fiction and that job one is to lay out the story as efficiently as possible. Macdonald was almost always an economical writer—a trait that probably arose in part from the fact that he wrote longhand—and he knows how to move a story along. If anything, Macdonald is vulnerable to the opposite criticism; he never met an unbelievable coincidence he didn’t like if it helped to quickly advance the plot.

In chapter one we meet our protagonist, Dr. Robert Branch, a junior professor at the university, and his friend Alex Judd, another professor. They have driven to Detroit to try to enlist in the Navy, which gives Macdonald an opportunity to set the stage through their good-natured banter. Both are anxious to do their part in the war, although Branch’s plans are frustrated by an old injury that left him practically blind in his left eye. The injury later becomes important for a number of reasons, but for now it provides the reason why Judd passes the physical and Branch does not. Since Judd will be leaving the university shortly, he confides in Branch his concerns about a possible Nazi spy on campus, and mentions a German professor, Dr. Schneider, as the focus of his suspicions. The underlying mystery is laid out by page twelve (page references are from the Mysterious Press trade paperback edition).

And Macdonald is not done yet. It just so happens (remember what I said about coincidence) that in the next six pages, he packs in two more developments.

First, Branch learns that Ruth Esch, his German fiancée who has been missing for the last six years, has been hired to teach conversational German at the university. This comes as a bit of a surprise because (1) for six years he has not known if she was alive or dead and (2) she has made no efforts to contact him. Macdonald leaves us no time to puzzle about their communication issues because on the next page he encounters Dr. Schneider himself, who (1) confirms the news about Ruth Esch, (2) tells Branch that she is arriving on the nine o’clock train that evening and (3) invites him for dinner so they can go and meet her train together.

Practically nothing happens on page 19, which comes as a relief to a reader struggling to absorb all the information.

In Summary

The opening chapter reads better than the summary would suggest. Branch has not begun speaking in the mock-heroic overeducated phrasing that is one of the book’s most glaring weaknesses. I found only one example in chapter one, but it was glaring enough that Peter Wolfe calls Macdonald out on it, (“Arbana is the Athens of the West and McKinley Hall is its Parthenon and I am Pericles”).

Macdonald is already displaying a sound instinct that what the reader of a mystery wants is the problem. It can become more complicated, or even morph into a different problem, but until we bring the problem onto the stage, the story has not really begun. At the end of chapter one, Macdonald’s tale is well underway.

In chapter two we will get to know Branch’s mysterious fiancée, Ruth Esch. Ready or not, here we go.

Recent Comments