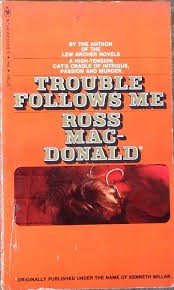

TROUBLE FOLLOWS ME

Part Six

WELL, IT’S ABOUT TIME

Sayre’s Law: The contest was so bitter because the stakes were so low

The book has strong points, but it could have been better with a good revision. I will discuss the particulars of how a rewrite could have helped in another post; but there is a more general problem that, if Macdonald had not been in such a hurry, he might have noticed, that could have been easily fixed.

He set the book at the time it was written, in 1945. At that point in the war the fighting was still hard and bitter—1945 witnessed two of the bloodiest campaigns of the Pacific War, Iwo Jima and Okinawa. But 1945 was about beating a stubborn, defeated enemy into submission. The tide turned in 1942. No well-informed person, not even the fanatical Japanese leadership, thought the war could be won. Their only strategy was to make their own defeat as costly as possible to the United States in the hopes we would become discouraged at our losses and sue for peace. (This is from the same people whose calculations about the American character brought you Pearl Harbor.)

It is not a spoiler to disclose that the book is about a spy ring passing along ship movements to the Japanese. If you made it as far as page nine, that particular MacGuffin is in play. (It might have been amusing to write a book where the protagonist chases a spy ring for 210 pages and finds out that it never existed, but that requires a certain level of irony, and an indifference to ever being published again, that Macdonald lacked.)

It would have made a huge difference in 1942 if the Japanese could have anticipated the movements of the American fleet. The fact that our codebreakers could predict that the Japanese would strike at Midway rather than half a dozen other places was a major part of the American victory. By 1945, although the war had increased in intensity, the geographic scope of operations had narrowed from a defense perimeter of 20,000 miles to 1,000 miles. Operations in 1945 did not achieve any strategic surprise and no one expected that they would.

It is interesting to note that The Dark Tunnel shows the same timing fault, although to a lesser degree. The book opens in September of 1943, after the Allies had recaptured North Africa and Sicily and were landing on the Italian peninsula. The Germans didn’t need spies to learn American mobilization plans by then—they just needed to look out the slits of the bunker, or up in the air.

So Why?

It was not because Macdonald wouldn’t have agreed with my summary of the war. As one character says to a member of the spy ring in chapter 13:

“Before long you’re going to be out of a job . . . We’ll tell you ahead of time where our ships are going to strike, and you won’t be able to do anything about it . . . because there will be no Japanese warships left. There will be no Japanese airforce left. Perhaps there will be no Japanese cities left. The Japanese islands will be a sad place.”

The Take-Away

Was there a good reason to set the book so late in the war? I am stumped. His choice is a good example of the importance of revision. It was not a terrible idea to set the book in 1945; but it would have been a better one to set it earlier. Revision isn’t often a choice between awful and great—it’s usually a matter of good, better, and best. As authors we don’t always get to Best, but we can all try for Better.

Recent Comments