BLUE CITY

PART ONE

WHAT THE CRITICS SAY

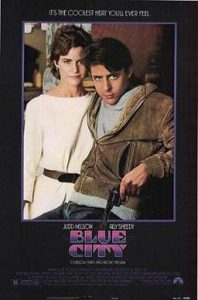

Blue City, Macdonald’s third book, is the first to have even a toehold in modern memory, and not because of the 1986 movie that bombed so badly it sank the career of not only the director but several of the stars.

“Blue City is not merely imitation Hammett, it is introductory Macdonald.”

Robert B. Parker, writing in his introduction to the 1987 hardcover reprint, says that although the general plot is deeply indebted to Hammett’s Red Harvest, Hammet’s theme is social and political. Macdonald’s story is ultimately personal for his hero, and it prefigures Macdonald’s lifelong obsession with lost fathers and broken families.

“The chief failing of this early book is a lack of subtlety in the portrayal of evil.”

Jerry Speir, in Ross Macdonald, devotes only three pages, calling it “Macdonald’s most violent novel,” a fair point, and anticipates Parker’s 1987 reaction to the book, noting that “It marks an incremental step away from a concern for monolithic evil and toward a smaller, more human and personal scale.”

“Blue City is the angriest book Macdonald ever wrote, and the most violent.”

Bernard A. Schopen has little time for the book because the protagonist is “impossible to take seriously, as is the novel he narrates.” He quotes with approval the New Yorker review which called the book, “very, very tough, and a little silly, too.” But Schopen sees merit as well. Macdonald’s portrait of social conditions in his fictional town are “sharply etched and recognizably real.” The action flows naturally from the personality of the protagonist. And, rarely in Macdonald’s work, the hand of coincidence lies lightly.

“Blue City introduces the theme of exile and return, which Millar would develop with increasing complexity.”

Matthew Bruccoli otherwise did not care for the book, noting that the idealism of the narrator-hero is at odds with his frequent and sometimes gratuitous brutality. He notes that Blue City appeared the same year as I, The Jury, by Mickey Spillane, a book that Macdonald detested. Bruccoli speculates that in the future, Macdonald began to tone down the violence in his own books as a reaction.

“Millar’s obligation to Hammett is not elegantly paid in Blue City, but the intention is robust.”

Michael Kreyling, in The Novels of Ross Macdonald, agrees with the other commentators about the flaws in the book, but sees promise as well. He analyzes the book as a retelling of Hamlet, with the protagonist seeking to revenge the murder of his father. A hard-boiled Hamlet sounds outlandish, but Wolfe backs up his theory with a lengthy textual analysis. And we should keep in mind that whatever weaknesses he shows in his early books, Macdonald held a Ph.D. in English Literature and studied with W. H. Auden. If anyone had the background to pull it off, he did.

“Blue City is too closely tied to the cult of the hard-boiled.”

Peter Wolfe, in Dreamers Who Live Their Dreams, disagrees with Schopen about the characters being well-drawn. Wolfe is a close reader of Macdonald and has good things to say about most of his works. Blue City, not so much. Wolfe does not so much object to the violence, recognizing that a certain measure is inherent in the genre, but reacts to the hero the same way readers of Virgil react to how Aeneas is portrayed in the latter part of The Aeneid, “No real person, Johnny Weather is a metaphor for a kind of simplified maleness . . . The unrealistic claims made for his powers rule out dramatic conflict. Nobody stands a chance against him.”

A word from the writer himself

“It was about a town where I had suffered, and several of the characters were based on people I hated . . . It was a substitute for a postwar nervous breakdown.”

Macdonald wrote the book partly as an experiment in style, and partly to put food on the table. He did not include it on the list of books he was proud of. It was written in only a month. But some good came of it all. When Macdonald’s first publisher declined the book, he wound up with a much better publishing house, Alfred A. Knopf. That was the beginning of a relationship that would last for the rest of his career.

Should we be talking about it?

It is impossible to appreciate the leap Macdonald made with The Chill unless we follow the steps of how he mastered his material. Blue City is crude, but it is also vigorous and suspenseful, and it is the beginning of his lifelong obsession with homecoming and finding one’s place in the family.

Recent Comments