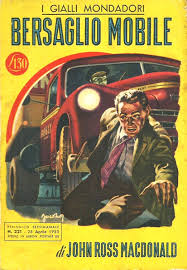

THE MOVING TARGET

Part Ten Spoiler Alert

WHAT’S NOT SO RIGHT ABOUT IT?

Characterization

The Moving Target is not a locked-room mystery or a police procedural; it is a drama arising from the personal circumstances of the characters. What grades will be give student Macdonald for his submission to the Advanced Mystery Writing course?

- An “A” for Elaine Sampson. Granted, she is a bit one-dimensional but that fits her role as a relatively minor character. Making her a secondary character where her husband has been kidnapped is a shrewd narrative move. From the outset we accept her as a useless outlier, which underlines Macdonad’s presentation of the family as one where the parents have abandoned the children. By contrast, her stepdaughter Miranda is at Archer’s side at every turn, doing the work of the older generation. Elaine and Archer speak only three times, none of them at length, and one of them is after the case is over. The possibility that her paralysis may be faked is a stroke of genius. The fact that we can entertain such a bizarre possibility is telling.

- A “B-“ for Taggert. Macdonald gives us some outward mannerisms but never addresses the man’s internal conflicts. Graves mentions how it is hard for young men to come back from the war and assume lesser jobs, but we are never shown how this relates to Taggert, if it does. We have no sense of what drives this man. I would be harder on Macdonald if Taggert did not turn out to be one of the kidnappers; I respect that he did not feel he could present Taggert more fully without tipping his hand. By the time Macdonald reaches full artistic maturity he will be able to do just that.

- A “D-“ for Miranda. Macdonald always struggled to create credible women characters. The fact that he and his wife did such a spectacularly bad job of raising their own daughter, Linda may not be a coincidence. Miranda is burdened with being the Bad Girl, which means that she must throw herself at Archer repeatedly and for no reason, so that Archer can demonstrate his sense of superiority. Her attempts to seduce Taggert are plausible enough, even in the face of competition from Betty Fraley. Her lack of sympathy for her father, although it is probably well-deserved, hardly helps us think well of her. And although her father was a busy man, there is no sense that he was abusive or that he deserves to be frozen out of Miranda’s heart. Then Macdonald doubles down on the implausibility of her character in Chapter 25 with what can only be described as the most unconvincing display of a psychotic episode I have read in a long time. To make it worse, Macdonald did no foreshadowing to prepare us. The most I can say is that this chapter occurs at a point when we are too caught up in the plot.

- An “F” for Graves. Because he is the ultimate villain, this failure is two-fold. Graves is unconvincing as a character, and the explanation for the crime fails to hold water, as well. Graves has a successful law practice. If Miranda marries him he is well-off now, with every prospect of being worth several million when the aged, dissolute Ralph Sampson dies. He does not need the money. Taggert would be the better candidate. The fact that Graves tries and fails multiple times to convincingly explain what he did is telling. The key to the solution of this book is a gratuitous killing.

- Peter Wolfe makes the same point. “Graves is the book’s least plausible character . . . . Graves has neither the need nor the temperament to kill for money . . . That he repents the evil so soon after performing it suggests that Ross Macdonald doesn’t believe it himself.” If Wolfe is correct, and I think he is, where are we left?

Structural Issues

The book does a fine job of creating a complicated family dynamic but lacks a sense of drama in how to resolve the conflicts. The family patriarch and the center of Archer’s concern never appears in the book except as a corpse. The plot gives no opportunity to see him as a person. And the little we know does not make us like him. Organizing a book around the rescue of someone who no one believes is worth rescuing is hard work.

Why the quickie marriage to Miranda? Archer puzzles about this but gets no good answer—I suspect because there is none. If Graves was afraid Ralph Sampson would disinherit Miranda, as unlikely as that seems, why antagonize Ralph by precluding a chance for a big wedding where the father could give away his only remaining child? It cannot have been a lawyer’s ploy to keep Miranda from testifying against him because she knows nothing. Miranda is impulsive enough to like the idea but it’s one more stress on the credibility of the story.

Peter Wolfe points out plotting problems. Macdonald writes several scenes in chapter 6 where he follows Faye Estabrook and masquerades as an exterminator that have nothing to do with the plot and could have been cut. Wolfe also points out that there is no reason for the lengthy scene where Archer feeds Estabrook alcohol and that the book could have been significantly shorter without any loss of narrative cohesion.

A more serious criticism Wolfe makes is that Macdonald’s ignorance of drugs, describing several characters as being in the throes of painful withdrawal from marijuana and also describing a professional driver as smoking marijuana on the job.

For my own part, Macdonald displays a sketchy knowledge of guns. Graves describes in detail his pair of .32 target pistols. Why a pair? They are for target shooting, not duels. Why that caliber? Pistol competitions use .22, .38. and .45. The .32 is an arcane little peashooter of a caliber, with none of the convenience and economy of the .22. I cannot swear that no one ever made a “target” pistol in .32 caliber but I would be surprised if they did. The point is a small one, and ballistics does not figure into the story, but it threatens our willing suspension of disbelief.

Why bother?

At the end of my own Cold July, my detective wonders whether he was right to take on the case in the first place. Although I am satisfied it was the right ending for that book, the ending bothered me because mysteries are about how the detective sets the world right. I sometimes call it an anti-mystery.

After finishing Cold July and re-reading The Moving Target, I find myself asking the same question. If Archer had never been hired, what would have happened? If the kidnapping had gone smoothly and the ransom paid, Taggert and Betty would have disappeared with the money and Ralph would have come home alive. Claude would have been able to keep his side hustle with the illegal immigrants. If Taggert disappeared, Miranda would have more readily chosen Graves, whose career would not have been ruined. The only person who benefits from the outcome is Elaine Sampson.

It is hard to escape the conclusion that Archer did more harm than good.

Recent Comments