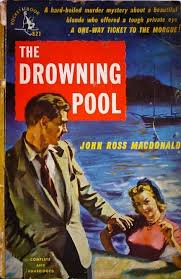

THE DROWNING POOL

Part Two

GETTING OUR FEET WET

Short Biographical Interlude

This blog is about Ross Macdonald’s books, not his life, and I refer the reader to Tom Nolan’s unsurpassed biography on the subject. However, we need to keep a few facts of his life in mind:

- After taking a number of post-graduate courses, including seminars with W. H. Auden, he completed his Ph.D. dissertation. However, an academic career never materialized.

- Macdonald never intended to make a living at detective novels, but the needs of his family and his failure to complete a satisfactory draft of his mainstream novel, Winter Solstice, left him with few options. Nolan’s biography does not suggest that he ever went back to the Winter Solstice manuscript except to cannibalize it for The Galton Case. Macdonald’s feet are now firmly on the path of becoming the best detective writer he can be.

- At the time he wrote his first two Archer novels his daughter Linda was already showing signs of serious behavioral problems. Although he tried to minimize them, he could not ignore them. This will be reflected in a long string of alienated and disaffected daughters in his fiction.

- Macdonald was back from the war and settled firmly in Santa Barbara, fictional versions of which will become the setting of many of his books.

- Although still a young man, Macdonald has begun to suffer from gout and hypertension, and has been drinking heavily.

- His fraught marriage with Margaret Millar will not terminate but it is hardly a source of emotional support. Macdonald’s pessimism about the possibility of a positive romantic relationship will only increase as he gets older.

- Although Macdonald did not create Archer specifically to serve as a series character, subsequent events, including the disappointing sales of non-Archer books that are otherwise quite good, will move him in that direction.

The Opening

“If you didn’t look at her face she was less than thirty, quick-bodied and slim as a girl . . . The eyes were a deep blue, with a sort of double vision. They saw you clearly, took you in completely, and at the same time looked beyond you . . . About thirty-five, I thought, and still in the running . . . Her face was clear and brown. I wondered if she was clear and brown all over.”

By contemporary standards, this is male chauvinist objectification of the female body at its worst, an example of the demeaning effect of the male gaze. In 1950, especially in noir fiction, it was an expected element of the plot. My own view is that he deserves to be judged by the standards of his time, both socially and artistically. Compared to Micky Spillane he was a raging feminist.

We have just met Maude Slocum, Archer’s prospective client. She is coy about revealing her business and prefers bantering at first.

“And can you whip your weight in wildcats, Mr. Archer?”

“Wildcats terrify me, but people are worse.”

She talks in riddles, reluctant to get to the point, a standard narrative move early in mystery novels. I just did it myself in August Hearts. Private detective stories are often about sensitive personal situations, and it would be jarring if the client set out the problem in a concise, businesslike way. The last time I saw such a thing was the first appearance of Bridget O’Shaughnessy, the femme fatal in The Maltese Falcon. Her manner indicates to both Sam Spade and his partner that she was lying.

What is unusual about their interchange is Archer’s lack of patience with her meanderings. He is short and sarcastic with her multiple times in a fairly short chapter. But in fairness to Archer, clearly she is hiding more than she reveals.

- She and her husband of sixteen years live in a mansion on a mesa above the oil town of Nopal Valley.

- She intercepted a letter the day before, a typewritten letter to her husband informing him that she was having an affair. The letter was postmarked from a nearby more genteel town, Quinto.

- She refuses to answer whether the allegation is true but Archer doesn’t spend much time worrying about that.

- Although she doesn’t want her husband to hear the allegation, she isn’t concerned that he would divorce her. However, if he took the letter to his mother, Maude is certain that her mother-in-law would force him to do so.

- She has no idea who sent the letter.

- Although she and her husband (James) live in a mansion, the property is owned by Jim’s mother. The mother is very wealthy but keeps her son on a small allowance.

- Jim has no job and spends much of his time with amateur theatricals. At the moment he is busy rehearsing a play at the community playhouse in Quinto.

- Archer reluctantly agrees to look into this, accepting $200 as a retainer.

The penultimate paragraph of the first chapter is pure Macdonald:

“The letter and the twenties were side by side [on my desk.] Sex and money: the forked root of evil. Mrs. Slocum’s neglected cigarette was smoldering in the ash-tray, marked with lipstick like a faint rim of blood. It stank and I crushed it out. The letter went into my breast-pocket, the twenties into my billfold.”

Recent Comments