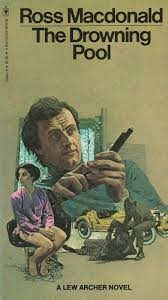

THE DROWNING POOL Spoiler Alert

Part Seven

Water Sports

When Archer comes to (an expression I am going to be using many times before we are through) he is in a straitjacket in Melliotes’ clinic. The doctor is in, along with a nurse, or at least a woman in a nurse’s uniform. After some tough talk on both sides, Archer is freed from the straitjacket but locked into a large hydrotherapy room, twelve feet high, with a glass skylight. They torture him with high pressure water jets for a few minutes and then, in the best tradition of villains, leave him alone.

Since the room is completely sealed by a single watertight door, Archer realizes that the only way out is the skylight. And that the only way to get to the skylight is to float up. He plugs the drain, turns on all the water jets, and waits for the room to fill. We never find out if he could have escaped through the skylight because when the room is nearly full the door simply blows open, flooding the building with thousands of gallons of water and knocking Melliotes unconscious.

Archer retrieves his clothes and a gun. In the course of letting himself out of the building, he hears Mavis. He retrieves the keys from Melliotes and unlocks the cell where she has been held. He urges her to go to the airport and fly to Mexico but she wants him to go with her.

Before that can be resolved, Kilbourne shows up. Archer forces him into the cell where Mavis has been held. He gives Mavis the gun and tells her to guard him while Archer goes outside to confront Kilbourne’s chauffeur. It is not clear that Archer knew he was there or why this move is even necessary. But it doesn’t matter. It should not surprise the reader that by the time Archer has walked outside, Mavis has shot her husband dead.

Mavis offers herself to Archer as a very wealthy widow, saying that if he cooperates with her they can go to Mexico and share all of Kilbourne’s money. Archer declines. He advises her to phone the police and turn herself in, pleading self-defense.

Next Stop, Hollywood

Archer meets with Mildred Fleming, the woman whose chatty letter he had seen in Maude Slocum’s desk. Mildred and Maude were roommates years ago. She confirms what every reader has suspected, that Maude and Knudson were lovers and that Knudson is Cathy’s biological father. The new information is that Knudson wanted to marry her when they found out she was pregnant but Knudson had a wife who refused to give him a divorce.

But the Story is Back in Nopal Valley

Archer goes back to Antonio’s and retrieves the ten thousand dollars. He gives it to Gretchen Keck, the girlfriend of Reavis, telling her, falsely, that Reavis wanted her to have it. Archer explains that Reavis was not the killer, that he was killed because he had claimed that he was. He thought he was making ten thousand dollars for a murder he hadn’t committed in the first place. As he leaves, Archer reflects:

“The money wouldn’t do her any permanent good. She’d buy a mink coat or a fast car, study bibleand find a man to steal one or wreck the other. Another Reavis, probably. Still, it would give her something to remember different from the memories that she had. She had no souvenirs and I had too many. I wanted no mementos of Reavis or Kilbourne.”

Archer drives back to the Slocum house and finds James and Francis Marvell sitting on his bed playing chess. Slocum’s voice is “weak and peevish.” He complains that his daughter has turned against him now and wishes to be with Knudson. Slocum has realized that Maude hired Archer and accuses Archer of helping Maude to murder Mrs. Slocum. Archer does not respond; he decides that Slocum has only a tenuous hold on reality and that arguing with him would do no good. Archer thinks to himself that Slocum must have driven his wife to suicide with accusations that she had killed Mrs. Slocum.

Archer leaves Slocum and Marvell together and seeks out Cathy Slocum. She admits that she is the one who killed her grandmother and that she tossed Reavis’ chauffeur’s cap into the pool as evidence that he was responsible. She admits that she also sent the poison pen letter. She claims to have hated her mother after seeing her and Knudson together and wanted to cause a divorce which would leave her and James Slocum together. And if her grandmother was dead and James and Maude inherited her money, Maude would want to divorce him anyway. She claims to have hated her grandmother for how she treated her father.

Archer decides he is not going to do anything with the information.

She knows that Knudson is her father and she is planning to go away with him when he moves back to Chicago.

At this point, with Archer ready to go, Knudson shows up and insists that Archer fight him. Archer attempts to decline but eventually they have a fistfight on the lawn to the point where Knudson is beaten.

They shake hands and Archer leaves.

Hi Neil. I just listened to the audiobook of The Drowning Pool on a 6 1/2 hour drive today. It was the only early Archer I’d missed (with the novels I’m now up to The Far Side of the Dollar) so it was interesting to go back to it, then read your blogs on it the same day.

It does seem a little like a couple of stories sort of stapled together, one a Hammett-like “thrilling detective” yarn and the other a proto-Macdonald intergenerational unraveling. The latter seems incomplete; I wanted a more realistic exploration of Cathy’s response to all that trauma moving forward. But then again I’m comparing it to his later further development of themes introduced here, after he’d had to examine his own family pathology. It’s certainly fascinating to view the girl’s story through the lens of Macdonald’s subsequent struggles with his own daughter, and some of the novel’s foreshadowing of his own family’s tragedies (brilliant teen daughter struggles with promiscuity and winds up killing someone!) is uncanny.

Some of the Chandleresque wisecracking at times seems labored, and occasional over-intellectualization is still sprinkled into the dialogue (doesn’t Cathy mention Coleridge at one point?). But to me the most jarring element was Melliotes’ little cackling assistant – where the hell did she come from? I mean, I enjoyed her creepy/funny interlude, but she seemed to have invaded from a different book (and genre) altogether. Overall though, I found it to be an enjoyable book on its own terms, and interesting as a step in Macdonald’s development.

Before I close this, I also wanted to thank you for your recommendation of The Archer Files. As I read through Nolan’s Macdonald biography, I’m stopping whenever I get to a point at which he had a short story published, reading the story then to fit it into the context of the author’s life. And now I’m holding off on reading the Far Side of the Dollar until I get to around 1964 in the biography. So thanks for contributing to what’s become a very gratifying exploration of this intriguing author’s life and work.

Dear Bill,

It’s always a pleasure to hear from you, or anyone else who has substantive comments (we won’t talk about the bizarre spam I get that never gets on the site–suffice to say that I have missed my chance to diversify by hosting photographs of Israeli prostitutes).

Your observation about The Drowning Pool as derivative of Hammett is spot-on. Macdonald owed a great debt to both Hammett and Chandler in his early Archer books, and he freely acknowledged it at the time. If you wanted to write intelligent crime fiction in the fifties, those two were your models. Eventually, as he matured as an artist he outgrew them. The popular term is “finding your voice.” After a dozen novels of my own, I find the phrase less helpful than I did forty years ago. It may refer to nothing more than the point when critics stop saying that you write just like so-and-so. Whatever it’s called, it refers to a real thing, a state of creative autonomy of the artist, and he certainly achieved that.

Yes, the lack of character development of the young daughter is a flaw. If you were following my posts on The Way Some People Die you would see my same complaints about Galley Lawrence. In his early books, Macdonald was content to do the usual thing and make the killere the least likely suspect, someone the reader overlooked. In his maturity he understood how that led to unsatisfying fiction, as you point out. He realized that a good detective novel ought to do the same thing as a good novel–leave the reader with an understanding of the character of the key figure. And of course the most important figure is the killer.

Bill,

I wanted to comment on the part of your post about Macdonald’s “wisecracking” but I thought it deserved a separate comment. In his early books, the wordplay of Macdonald’s protagonists is sophomoric. He hasn’t broken the vice even in the early Archers. Reportedly, the first step towards the cure was the day his wife told him that his criminals talked like college professors, and he took it to heart.

His urge for snappy patter is imitative of both Hammett and Chandler, especially the former. But Hammett really was a private eye, and Macdonald had an academic background. Fortunately he learned to try to stop writing about what he didn’t know and this irritation disappears from his later books