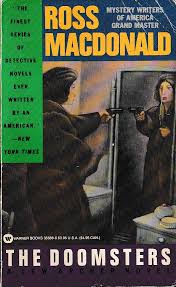

MACDONOLD AND FATALISM Spoiler Alert

“She Blamed it all on the Doomsters”

Mrs. Hutchinson continues with her story about Alicia Hallman. The evening she died, Alicia told Mrs. Hutchinson she had to go out— she claimed she had received a call from Berkeley, where Carl was attending college, that upset her. But her mood was more than her usual distress; she felt her family had deserted her and that none of them loved her. She said she was thinking of killing herself. She blamed it all on the Doomsters, which was her name for the evil forces of fate that she felt had turned the world against her.

Mrs. Hutchinson could have acted, but she failed to do so. She watched as Alicia put on her mink coat, loaded her revolver, and called for one of the ranch employees to drive her. The last time Mrs. Hutchinson saw her was about seven o’clock. The employee was back within an hour; he said Alicia had instructed him to let her off at the pier and leave her there.

As far as everyone’s whereabouts,

- Senator Hallman and Jerry were in Berkeley, looking for Carl.

- Zinnie was staying with some friends in town.

- No one knew where Carl was and no one could be sure that he wasn’t in town.

- Grantland came to the ranch at midnight. He tried to calm Mrs. Hutchinson down, saying that Alicia would probably come home—but just in case she didn’t, she shouldn’t say anything about the gun; she should simply say that Alicia slipped out without her noticing it. And she also shouldn’t say that he had been out to talk to her that night.

A Digression from the Plot

One of the pleasures of reading Macdonald is that you are in the hands of a learned man. He knew English literature, he knew Freud, and he knew his Greek mythology. He knew how the Greek understood the Fates as three actual gods. (The ancient Greeks were so misogynistic that the Fates are always depicted as female.) One wove the fabric of a person’s life, the second gathered the cloth together, and the third cut the thread, determining the day the person would die. They were merciless and implacable, and there are very few stories where they ever changed their minds. The only one that comes to mind is a late play, not from the classical folklore tradition. They were all-powerful; Zeus himself was once challenged to save the life of a favorite human and even he admitted he had no power over what the Fates had decreed.

The myth of the Fates was a deep part of the culture of ancient Greece. The best-known example is Oedipus. Oedipus is fated to murder his father and marry his mother. He, his birth parents, and his foster parents take steps to avoid what the Fates have decreed. Their efforts are useless. Macdonald expressly addressed the Oedipal plot in The Three Roads

and never suggested that the protagonist there could have changed his fate. His only choice was the one the ancients understood—how he faces up to the inevitable.

The Causal Continuum in Philosophy

The one extreme is fatalism, the view that the result will occur no matter what anyone does. The opposite pole is free will—nothing is determined and actions have no necessary consequences. In the middle are various forms of determinism—that although our actions may be determined by past events, we are still free to choose.

What does this mean for fiction?

The Greek playwrights, by and large, accepted fatalism and turned it into wonderful drama by depicting the protagonist’s struggles against his fate, and then his acceptance. Fiction based on a strictly fatalistic view is hard to imagine in a modern context; at least, not unless it is a setup for a surprise twist at the end, in which case it is no longer fatalism at all. If your premise was that no matter what the protagonist does he will kill his wife at 11:45 with a blow to the head from a frying pan, the story would be neither readable or even writeable.

Modern fiction often flirts with the opposite extreme of unbridled free will, but unless the writer is very clever, the result if often frustration. Yes, character were free to do that—but why did they do it? We don’t like it when characters make important decisions at random. We want to be convinced that there are reasons, which in terms of character means providing motivation. There are certain modern practitioners who write stories with unmotivated major action, but they are in the minority. Readers of popular fiction want to know why. it’s not an unreasonable expectation.

The active battleground is in the middle—some form of what philosophers call strong or weak determinism. The character has reasons, even compelling ones, but remains free to act on them or not.

Macdonald is a strong determinist, especially where family influences are concerned. The grip of the past, especially past crimes, is relentless. Sometimes luck and the intervention of Archer can break the causal chain; more often they cannot. As President Bartlett’s wife said in The West Wing, “You can’t change the world. But it’s sure fun to watch you try.”

Recent Comments