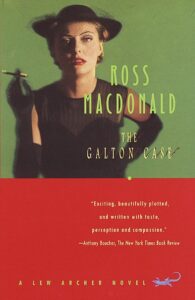

ROSS MACDONALD CAN BE VERY FUNNY

A Brisk and Entertaining Start

When we think of humor in the detective story, names like Donald Westlake, Parnell Hall, and Carl Hiaasen come to mind long before Ross Macdonald does. But Macdonald can write a deft comic scene when the story calls for it. He uses the opening of The Galton Case to skewer the rich, and especially the lawyers that serve them.

The story opens as Archer arrives at the law office of Gordon Sable, who has contacted him about taking on an investigation for one of his clients:

“The law offices of Wellesley and Sable were over a savings bank on the main street of Santa Teresa. Their private elevator lifted you from a bare little lobby into an atmosphere of elegant simplicity. It created the impression that after years of struggle you were rising effortlessly to your natural level, one of the chosen.

“ . . . Audubon prints picked up the colors and tossed them discreetly around the oak walls. A Harvard chair stood casually in one corner.

“I sat down on it, in the interests of self-improvement, and picked up a fresh copy of The Wall Street Journal. Apparently this was the right thing to do. The red-headed secretary stopped typing and condescended to notice me.”

After a brief conversation the secretary recognizes who he is.

“She relaxed her formal manner. I wasn’t one of the chosen after all.”

She informs him that Mr. Sable isn’t coming into the office but asked if Archer would mind driving out to Sable’s house.

“’I guess not.’ I got up out of the Harvard chair. It was like being expelled.”

Knowing When to Break The Rules

We all learned in Creative Writing 101 that a story must begin at the beginning, and the trick is to identify that moment. The true beginning of the story is when Archer arrives at Sable’s house on page 4. Except for a

two-page scene in Chapter 22, we are never at Sable’s office again, nor do we ever see the secretary after that. But so much of the book is about the deadly struggle between the wealthy and the poor, a playful introduction is exactly what is called for. As a commentator pointed out, a lot of the book is grim as Kierkegaard, and that is very grim indeed.

Let’s Meet Mr. December and Mrs. May

Macdonald is a paradox. In his mature works he displayed a passion for creating multifaceted, complex characters. His goal wasn’t just crime solving—he sought understanding of the people involved. He believed that the true person of interest in the book was the murderer, not the detective. In his best books, there are no black and white characters (except for Archer, who is hardly a character at all); only shades of gray. Terrible things are done for the best of reasons, and vice versa.

Yet the world of Ross Macdonald is littered with stereotypes. Let’s do a quick review.

- Male homosexuality is always associated with criminal behavior, moral degeneration, and a poor credit score.

- Female homosexuality is barely conceivable, and the rare times he introduces a character who might be a lesbian, she is promptly killed off.

- Adultery is punishable by death—if not that of the parties themselves, then of someone dear to them.

- Heterosexual sex is seldom worth the trouble.

- Divorce is invariably a one-way road to a lifetime of misery.

- The richer you are, the more corrupt are your motives; riches cause far more crime than poverty.

- Lawyers are only seldom honest, and almost never when they are in the service of wealthy clients.

- Black characters, no matter what the circumstances, will always turn out to be virtuous. This is also true for persons of Mexican descent, but not for Italians.

And now it’s time to remind you of one more, one we have seen most prominently in The Drowning Pool, The Ivory Grin, and The Moving Target.

- Romantic relationships between persons a generation apart never work. (This will be a surprise to an 87-year-old friend of mine and his 58 year-old wife of thirty years, but that’s their problem).

The story shifts, or rather begins, with Archer’s arrival at the luxurious rural home of Gordon Sable. The door is answered by an insolent, rough-looking man who seems wildly out of place as a household servant—and for good reason, as we will learn in a few pages.

Sable is a contradiction—a man of wealth and sophistication but (as we will learn shortly) henpecked by his much younger wife. For now it’s sufficient to know that she is young, blonde, willful, not very bright, and an out-of-control alcoholic.

Sable ushers Archer into his study. Even allowing for the detour at Sable’s office, we are only on page 5 and we are about to learn what the case will be about. Not a bad pace.

Recent Comments