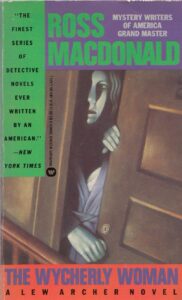

THE WYCHERLY WOMAN Part One

WHAT THE COMMENTATORS HAVE TO SAY

THIS INTRODUCTION WILL BE A LITTLE DIFFERENT

For every other book, there has been a good deal of material on the merits beyond summaries of the plots. This time my sources are nearly dry. I have some discussion to offer on how The Wycherly Woman fits into the canon, and I have included some quotes below. But there is little to offer by way of evaluation, except to say that Wolfe did not care for it and Schopen does.

The dearth of material, I think, stems from a core problem that I can’t discuss without a plot spoiler of gargantuan proportions. If you find Macdonald’s twist in this book to be unbelievable, as Wolfe did, it ruins the book. If you are prepared to roll with it, as Schopen did, you will appreciate a fascinating and deeply thoughtful mystery.

\ A PLEA FOR SOME SUSPENSION OF DISBELIEF

The private eye novel is inherently a little preposterous. It bears the same level of realism as the Rambo movies have to actual soldiering. Real private detectives mostly do skip tracing and review computer records. But no one wants to read about that. We accept that the private eye stories we love involve suspense, usually at least one murder, danger, some gunplay, and more sex than happens in real life. If you have reached this point in the blog, you have no trouble accepting how Archer routinely get leads by eavesdropping outside an open window or finding leads in abandoned luggage. I can’t persuade you to accept the twist at the core of this book. I can only tell you that if you can, you will be well rewarded.

“The success of the novel hinges on the reader’s willingness to accept a proposition that Bruccoli delicately described as ‘an unlikely twist.’ This proposition granted, however, the novel is marvelously moving.”

— Bernard Schopen, Ross Macdonald

The Wycherly Woman in Context

The commentators most discussed in this blog often lump Macdonald’s first four books together, despite the huge differences between them. The same writers also treat the novels of the early sixties as a group—The Wycherly Woman, The Zebra-Striped Hearse, The Chill, The Far Side of the Dollar, and Black Money.

“The books from The Wycherly Woman (the earliest and least successful of the group) to Black Money deal with tragic sexual passion. Some of the tragedy is caused by money; money cuts across the passion in all the books . . . The works published between 1961-66 grow more elaborate and complex . . . The Archers . . . broaden their human base, display new strengths, with The Chill and Black Money pushing to the top of the canon.”

–Peter Wolfe, Dreamers Who Live Their Dreams

“The Wycherly Woman is a neglected novel in the Archer series (never collected in a volume of three and ranked low by the novelist himself) but it operates as a subtle transition from the period of breakthrough to the inevitable next stage—arguably, Macdonald’s strongest sustained production: the wholesale social breakdown of the 1960s epicentered more often than not in his plots on a troubled daughter.”

—Michael Kreyling, The Novels of Ross Macdonald

Fun Fact

The original title was The Basilisk Look; presumably someone at Knopf earned their salt scotching that one. Although it might have been a hit with herpetologists.

Sales

Despite a few reviewers that were put off by the twist, the reviews were generally good. Sales were strong, including a condensed version in Cosmopolitan. It was reprinted in England. The publication coincided with a spate of translations of earlier works that gave Macdonald an international audience as well as putting him on a firm financial footing.

Recent Comments