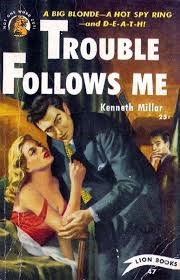

TROUBLE FOLLOWS ME

Part Two

What Do The Critics Have to Say?

Not So Much

Authors often compare their books to their children, with good reason. And like children, the firstborn often gets more attention, merited or not, than the later-born. Also, the attention tends to be sympathetic. The bar is lower for the first-timer.

Authors often compare their books to their children, with good reason. And like children, the firstborn often gets more attention, merited or not, than the later-born. Also, the attention tends to be sympathetic. The bar is lower for the first-timer.

- Matthew Bruccoli, in Ross Macdonald, gives it a single line, describing it as “another competent but unpromising work.”

- Jerry Spier, in Ross Macdonald, summarizes it on one page with no evaluation.

- Michael Kreyling, in The Novels of Ross Macdonald, covers the book in two paragraphs, with no evaluation.

- “Literate and exciting,” according to the New Republic reviewer at the time of publication.

- According to Anthony Boucher, the book showed “a God-given ability to write which has no business striking twice in the same family.” (A reference to Macdonald’s wife, the suspense novelist Margaret Millar).

“The morality of Trouble is not cheap or trite.”

Peter Wolfe, in Dreamers Who Live Their Dreams, devotes a full ten pages and concludes that Macdonald’s “powers of observation excel . . . but his dramatic motivation falls short.” Wolfe despairs at Macdonald’s “shabby” treatment of his women characters but admits, “The bright, crisp language of Trouble reflects both a sharp eye and tender heart; the narrative materials are well selected, imaginatively perceived, and carefully arranged.”

“The impact of the action is enfeebled by the conclusion.”

Bernard Schopen, in Ross Macdonald, compares it favorably to The Dark Tunnel, noting that although it still relies heavily on coincidence, the plot is much stronger. Trouble is a more ambitious book, and presents a serious subject, race relations, honestly and dramatically. But Schopen, like Wolfe, dislikes the ending, calling it “reversal for reversal’s sake,” and notes that in the preceding two hundred pages there is nothing that makes the resolution even slightly plausible.

“The most improbable thing was that the book was written at all.”

Tom Nolan, in his biography of Ross Macdonald, notes that despite the cramped conditions on the Shipley Bay, Macdonald produced not only this novel but a children’s story, four short stories, hundreds of letters to his wife and dozens of plot ideas. Nolan is on to something; what is wrong with the book is largely that it was rushed to print in haste. I will explore this further when we discuss the ending. His verdict: “an often-awkward blend of graceful passages and bizarre locutions, well-evoked scenes and wild improbabilities.”

“The complex plot is marred by monstrous coincidences.”

The Ross Macdonald Companion, by Robert L. Gale, is a reference work rather than a literary analysis, but at times we hear the author’s views when he summarizes a novel. Gale praises the book for clever pacing and its “sympathetic handling of racial tensions following the 1943 Detroit riots and his realistic portrayal of justifiably suspicious, nervous African Americans.” He also notes sequences that he justifiably describes as “semi-idiotic.”

My Own Introduction

It is flawed in much the way The Dark Tunnel is flawed, but much less so. Tunnel could not have been a better book; there is nothing wrong with Trouble that a good rewrite could not have fixed. It grapples with a serious subject, race relations, at a time when it was not a fashionable topic for popular fiction generally, and even less so in genre fiction. Macdonald’s brain is not where it needs to be to produce his strong work, but his heart is already in the right place.

And the last word from the author himself

“It’s going to be a strange book . . . I don’t like it but I’m sort of fascinated by it . . . . God knows what to make of it, I don’t . . . As long as it’s good enough for the trade.”

Ready or not, here we go.

Recent Comments